Standing on the shoulders of giants

Kirsty Coventry will today be officially sworn in as the first female President of the IOC. Yet, until 1981 women were not even allowed to become members. Philip Barker traces how things changed

There are now 110 members of the International Olympic Committee, 48 of whom are women.

It may, therefore, come as something of a surprise to discover that in 1983, the year President-elect Kirsty Coventry was born, the organisation she is about to lead had only three women. The IOC membership was entirely male until October 1981 and had been so since its foundation in 1894.

Then at the 1981 IOC Session, Finnish athlete Pirjo Haggman and Venezuelan equestrienne Flor Isava-Fonseca became the first women to be admitted to what has been described as the “most exclusive club” in world sport.

The IOC had been founded with the mission of reviving the Olympic Games for the modern era. The driving force was French nobleman Baron Pierre de Coubertin, who like many of his generation, consistently opposed the participation of women in the Games. It was perhaps unsurprising that under his leadership, membership of the IOC was drawn exclusively from men of a certain age.

For many years after, the only women were administrative secretaries, including long-serving Lydia Zanchi, who first worked for the IOC in 1929.

Members were co-opted rather than elected, the very same term used in the gentlemen’s clubs of London which had provided the inspiration for the initial structure of the organisation.

Yet as the 1980s began, dramatic change was in the air.

Spaniard Juan Antonio Samaranch, was elected as President a few days before the 1980 Moscow Olympics began. He was 60 years old and seemed an unlikely revolutionary. He had been IOC member since 1966 and was Spanish Ambassador to the Soviet Union,

The first public showpiece event of his Presidency was scheduled to be at the end of September 1981. The annual IOC Session was to be accompanied by an Olympic Congress in the German spa town of Baden-Baden. Samaranch promised, “A Congress of change and therefore of hope. This change is nothing but a reflection of the changes taking place in our society. We must not remain inflexible. This would be highly dangerous for our organisation.”

At the Congress, 1964 Olympic women’s discus champion and Romanian Olympic Committee vice-president Lia Manoliu made a clarion call. “Let us give to woman (sic), the possibility of proving that she can assert herself in administration and management with the same success shown in high performance sport,” Manoliu told delegates. “Access to these areas by women would give her the economic resources and power of decision which at present belongs exclusively to man.”

In fact, changes in the composition of the IOC had already been discussed a year earlier at the first Executive Board meeting convened by Samaranch after his election. “The President would encourage the election of women to the IOC,” stated the official minutes.

The previous President had been Irish peer Lord Killanin from 1972 to 1980. A supporter of the introduction of women members, he later revealed that “in one instance, the current member withdrew his offer of retirement when he heard he was to be followed by a woman.”

In 1973, a handful of women were permitted to speak at an Olympic Congress in the Bulgarian resort of Varna. The gathering was condemned in Sportsworld magazine as “four days of mostly sonorous talk.”

Afterwards even the official Olympic Review admitted “Much criticism was directed at the IOC, accusing it of closing its doors to women representatives.”

A questionnaire was sent to National Olympic Committees and International Federations. The responses served only to confirm the reality. The only woman in charge of an Olympic sport was Inger Frith, the President of World Archery (then known as the International Archery Federation).

Killanin had identified some potential female members. These included American figure skater Tenley Albright, an Olympic gold medallist in 1956. Albright had forged a career as a surgeon and apparently felt she did not have sufficient time for the role.

The situation was further complicated by the peculiar nature of the organisation. Members are described in IOC documents as “neutral persons”. These represent the Olympic Movement in their respective countries rather than the other way round. There was not an IOC member in every country but in some cases there were more than one in the same country.

Killanin had also been keen to invite Bulgarian official Nadia Lekarska to become an IOC member, For this to be possible, the incumbent, Colonel General Vladimir Stoychev, a competitor at Paris 1924, would first have to step down. Although an octogenarian, he showed no inclination to do so. “It was simply not possible to find the vacancies for the candidates and that is why I failed before my term of office came to an end in Moscow,” Killanin told his IOC colleagues in Baden-Baden.

Nowadays, a specific IOC Membership Commission led by Britain’s Anne, Princess Royal is responsible for recommending new members, At that time the process was more opaque, the result of discreet conversations behind the scenes.

The ground was laid for the first woman member when Samaranch visited Finland in May 1981. The records of the Center for Finnish Sports Culture reveal that Finnish Olympic Committee President Juuka Uunila proposed Haggman. Uunila had previously been head of the Finnish Athletics Association, so had come to know Haggman in her days as an athlete.

In 1980, Haggman competed at her third Olympics. Her best Olympic performance had come in 1976 when she finished fourth in the 400 metres, missing a medal by just 0.01 seconds. She had also won 4x400m relay silver at the 1974 European Championships in Rome and completed the 100m/200m double at the 1975 World University Games in the same city. While competing, Haggman also studied for a degree in sports science and became a teacher.

“It was Uunila who first asked me if I was interested in the position.” Häggman confirmed. It was arranged for her to meet Samaranch at the European Boxing Championships in Tampere. “Samaranch made a very positive impression on me during our discussion,” Haggman revealed.

It was agreed that Paavo Honkajuuri, an IOC member since 1968 and one of two from Finland, would stand down in Baden-Baden. “Pirjo Haggman’s IOC membership was well received in Finland as a confirmation of the country’s prominent role in women’s enfranchisement,” said the Center for Finnish Sports Culture’s special researcher Vesa Tikander. In 1906, Finland had been the first European nation to allow women to vote.

This point was not lost on Honkajuuri. In his farewell speech, he “wished to state his pleasure at having two women members of the IOC. He noted that it was 75 years since women in Finland had the right to vote in Parliamentary elections. He felt it a fitting way to commemorate this event by having a woman from Finland as the first woman IOC member.”

Haggman was still in Espoo. She had just completed taking an orienteering lesson at her school when confirmation of her selection came through. “I have been waiting for a decision but was a bit pessimistic,” she admitted. “I had promised to accept if I was elected, and therefore I was hoping for a positive response.”

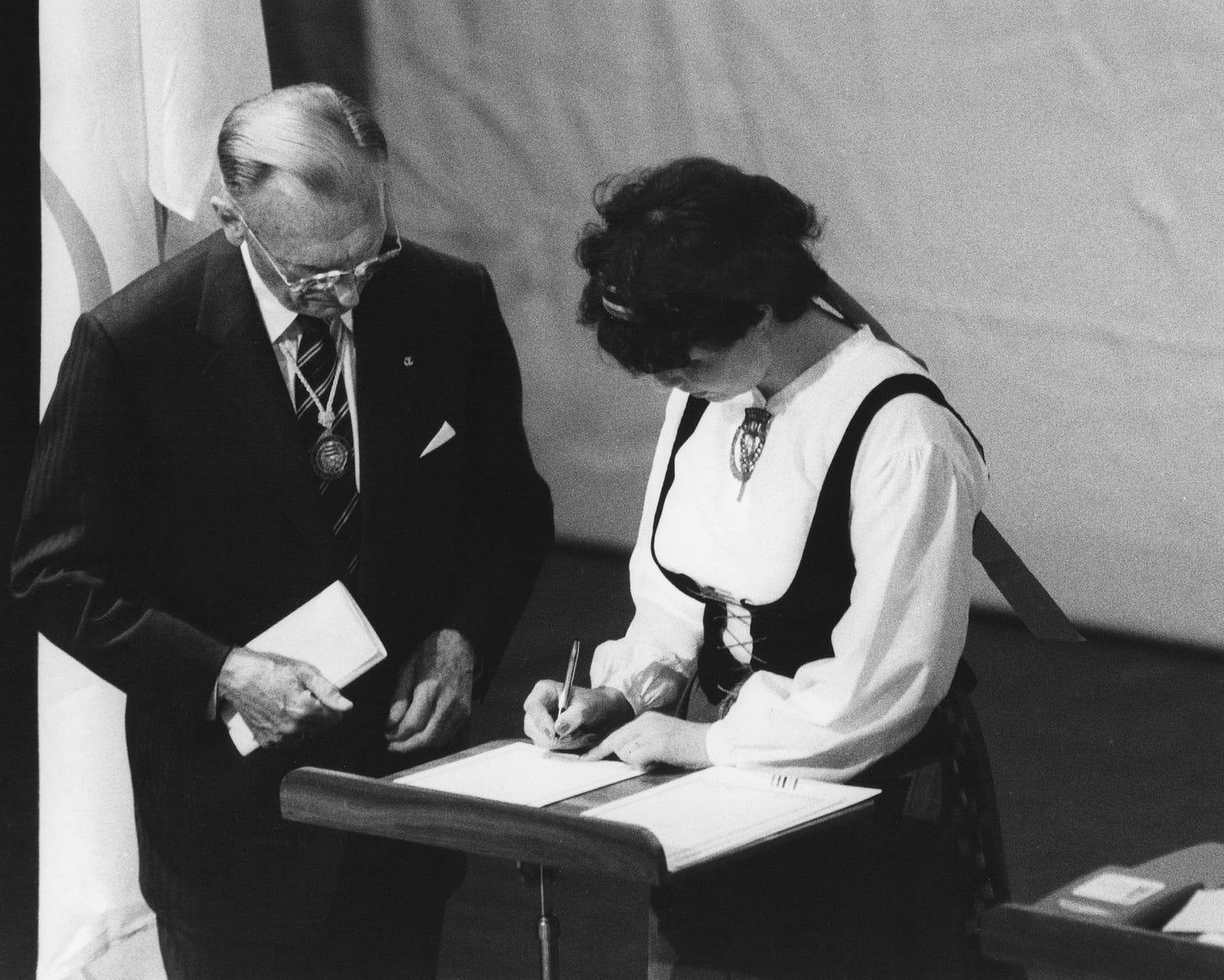

She had turned 30 only a few months before. She became the youngest member of the IOC elected since Prince Constantine of Greece joined in 1963 at the age of 23. The official swearing in was scheduled for May 1982 at the next IOC Session in Rome. Haggman wore traditional Finnish costume for the occasion. “The situation for women is not as good as it should be,” she said. “Men and women should be equal. In Rome we will see what the election means in real terms.”

In the same session, a report on the 1981 Congress demanded “greater possibilities should be made available to women in the administration of sports by the organisations concerned. The IOC has set the example and has already for the first time in its history, elected women members.”

The success of the athletes participation at Baden-Baden was followed by the formal establishment of an IOC Athletes Commission. Haggman’s fellow Finn, IOC member Peter Tallberg led the Athletes’ Commission. Haggman was soon appointed as vice chairman. The group included Thomas Bach and Sebastian Coe but only one other woman, rowing gold medallist Svetla Otsetova of Bulgaria. In those days, Athletes Commission membership did not include the status of full membership of the IOC.

In 1983, Haggman and Otsetova both visited the International Olympic Academy’s Young Participants session in Olympia as part of an IOC initiative on education. Haggman also worked as part of the IOC Commission for study of the Winter Olympic programme and Evaluation Commission for the Preparation of the Olympic Games. She also joined the Pierre de Coubertin Commission.

Since her election, Haggman had insisted that drugs in sport were “a real all-encompassing issue, the biggest problem.” At the 1986 IOC session in Lausanne, she called for the Medical Commission to “arrange for doping checks to be carried out not just at the Games but also during training.” Nowadays out of competition testing has become standard practice.

Haggman continued to play a role in the IOC, but in 1998, the organisation was rocked by the Salt Lake City crisis. There were revelations that some members had received inducements to vote for Salt Lake City as 2002 Winter Olympic host. When it emerged that Haggman’s estranged husband had been employed by the Salt Lake City 2002 Bidding Committee, she resigned from the IOC. “Her departure was particularly sad, she was not only one of the first women members of the IOC but she was the only Olympian to leave us in the wake of the scandal,” wrote IOC Executive Board member Kevan Gosper.

In a statement Haggman said: “From the current perspective, I am guilty of being rash and perhaps naive in my trust in other people. I have lost my ability to function as a constructive IOC member. My conscience is completely clear; I have not broken any Olympic oath nor violated IOC rules.”

At the time, Helsinki was bidding for the 2006 Winter Olympics and many felt she had come under pressure to resign. “In Finland, Haggman’s image did not take a too serious dent, many considered her resignation as premature, as there were worse [male] perpetrators in the 1999 scandal,” Tikander claimed.

The other woman who had joined in 1981 alongside Haggman was Isava-Fonseca. A tennis player in her youth playing as Flor Isava, she had won silver in the women’s doubles silver in the 1946 Central American and Caribbean Games in Baranquilla, partnering Marian Schlateger. In 1947 Isava founded Venezuela’s Equestrian Federation and later became its President. Although never an Olympian, she won seven national jumping titles and five in dressage. In 1964, she became a member of the Venezuelan Olympic Committee.

Her compatriot Jose Beracasa, a founding member of the VOC, described her as “a most able successor”. He stood down from the IOC to allow Isava-Fonseca to take the place. Samaranch was thought to have insisted on her selection. Some Venezuelan officials were said to have been put out by the lack of consultation.

Isava-Fonseca was 60 years old when she joined the IOC but was responsible for breaching the next barrier. “I spent nine years learning from the other members of the Olympic Committee,” Isava-Fonseca recalled later in an interview at the United Nations. “Then, I thought, we had managed to open the door for women as members of the International Committee, why not push open the doors to the Executive Board?”

When the election took place at the 1990 IOC Session in Tokyo, there were still only half a dozen women entitled to vote. These included Princess Nora of Liechtenstein, currently the IOC Doyenne as the most senior member and Anne, Princess Royal of Britain, who had joined in 1988,

It took four rounds of voting before Isava-Fonseca defeated Pal Schmitt of Hungary by 39 votes to 35. She “thanked the members for their confidence in her and said she would continue to work for greater representation of women in sport and sports administration. She emphasised that the IOC President had done much to help women.”

In the same year, Isava-Fonseca was awarded her country’s highest decoration, the Simon Bolivar Order, by Venezuelan President Andres Perez. She remained an IOC member until 2002 and then assumed honorary membership., She was described as “The eternal lady of the Olympics” by the VOC when she died in 2020 at the age of 99.

Amongst those who had elected her to the Executive Board in 1990 was Anita DeFrantz, another destined to play a significant Olympic role. DeFrantz had won rowing bronze at the 1976 Montreal Olympics for the United States.

When US President Jimmy Carter called for a boycott of the 1980 Games in Moscow, DeFrantz launched a legal action against the United States Olympic Committee in an attempt to allow those who wished to take part in the Games. It was in vain, but in recognition of her efforts, she was invested with the Olympic Order which was presented in Moscow. “I sometimes tease people saying I was the only American to receive a medal in Moscow in 1980,” DeFrantz has joked.

Los Angeles 1984 Olympic Organising Committee President Peter Ueberroth recruited DeFrantz with special responsibility for the Athletes’ Villages at the 1984 Games. DeFrantz served as LAOOC vice-president. The Games themselves made a huge profit.

The LA 84 Foundation was a charitable trust set up afterwards with a share of the Olympic proceeds to encourage sports participation and offer funding for coaching initiatives in Southern California. DeFrantz was put in charge and the Foundation flourished.

Her name was on a shortlist suggested by the USOC for potential IOC membership along with 1964 swimming gold medallist Donna de Varona and Ueberroth. Ultimately though, DeFrantz was chosen and co-opted during the 1986 Session in Lausanne.

Her next step came in 1991 when fellow American IOC member Robert Helmick, also a leading figure in international swimming, abruptly resigned from the Executive Board and the IOC. It was alleged that he had used his sporting connections for his own business advancement.

An election for the vacant Executive Board post was held shortly before the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. DeFrantz defeated Norwegian Jan Staubo and took her seat alongside Isava-Fonseca. For the first time, there were now two female IOC Executive Board members. DeFrantz had been a member of US Rowing’s task force on “affordability, accessibility and diversity” in the sport and also became World Rowing vice-president. In 1995, she led a new IOC Women and Sport Commission which “examined women’s present situation in the Olympic Movement and in the sports world generally,”

At the 1996 Centennial Olympics in Atlanta, DeFrantz called for “an increased number of women members of the IOC. Efforts must be made in IOC commissions and working groups, as well as in the IFs and NOCs commissions to have women appointed.” It set a target of 10 percent “of all the offices in decision making structures” to be held by women by the end of the year 2000. Sports Illustrated recognised that DeFrantz was becoming a major player by regularly listing her in their list of “100 Most Powerful People in Sport”.

In 1997 she was elected by acclamation as an IOC vice-president and in 2001 she announced her intention to run for the top job. “I have served the Olympic Movement for 24 years, which is half my life,” DeFrantz told the Washington Post. “I want to make sure the Games endure - that’s my responsibility as an IOC member. I believe I can fulfil my responsibilities best as President.”

Yet at the election in Moscow, she polled only nine votes and was eliminated in the first round. “I lost because I was American and because I was a woman,” she told the Official History of the IOC. Many suggested that her chance of election had been affected because she was one of the IOC members from the US at the time of the Salt Lake scandal. DeFrantz did eventually return to the Executive Board but not until the 2013 Session in Buenos Aires where Bach was elected President.

In the election, she was opposed by Prince Tunku Imran of Malaysia and Richard Pound of Canada. She defeated Pound by one vote in the second round. “I deeply appreciate this vote of confidence,” she told members.

In 2017, the IOC was back in South America in the Peruvian capital Lima. This time, DeFrantz was elected unopposed to the post of vice-president vacated by Australia’s John Coates. In the same year, she was inducted into the Los Angeles Coliseum Court of Honor. An inscription on the commemorative relief bearing her likeness pays tribute to her “long and distinguished Olympic career and her leadership roles”. It stands alongside a similar plaque for 1984 marathon champion Joan Benoit. They were the first women so honoured since the pre-war Olympic champion and all-round sportswoman Mildred “Babe” Didrikson Zaharias was posthumously inducted in 1961. In March this year, DeFrantz defied illness and flew to Costa Navarino to vote in the 2025 Presidential election.

It was as a member of the IOC Athletes Commission that Coventry had her first experience in IOC circles. It had been DeFrantz who led the Commission which introduced direct elections for the IOC Athletes Commission at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. “It is fitting that at the Centennial Games the athletes will have their first opportunity to vote, as we look to the future, athletes will have an important role in defining and resolving issues important to them,” DeFrantz wrote in the magazine circulated to athletes in the Olympic Village.

In the last dozen years, the Commission has been led exclusively by women. After fencer Claudia Bokel of Germany, ice hockey’s Angela Ruggiero of the US, Coventry and Finnish ice hockey player Emma Terho have all been in charge.

In 2013, when Coventry took her place on the IOC, the only other female member from an African nation was Beatrice Allen of the Gambia. When Coventry flew home to Harare after the IOC session, she was welcomed by traditional drums and dancing. Pupils and teachers from the Dominican Convent High School, her alma mater, presented a bouquet to recognise her achievement. “It is not just my success, it is our success, we broke down barriers,” Coventry told the welcoming party.

She is set to become the first swimmer to lead the IOC, but a generation ago another female Olympic swimmer was the de facto most powerful individual in the Olympic Movement, although never an IOC member. The late Francois Carrard, lawyer and later IOC director general, described Monique Berlioux as “the woman who had been the true and only boss of the IOC for many years.”

Berlioux swam backstroke for France at the 1948 London Olympics and worked as a journalist and filmmaker. She joined the IOC in the late 1960s, and worked in IOC media. In 1971 Berlioux was appointed director. The incumbent IOC President was American multi-millionaire Avery Brundage, but he preferred to live in the US, not in Switzerland. When Killanin became President, he also opted to remain at home in Dublin.

As a result, the day-to-day running of the Olympic Movement was down to Berlioux. In an era before formal structures had been established, she led negotiations in such areas as marketing and the negotiation of television rights deals.

Killanin described her as “formidable” and when the spectre of a boycott of the 1980 Moscow Games loomed, it was Berlioux that Killanin took with him to the White House and the Kremlin. “Do you want me to become more unpopular with the members than I already am?” Berlioux told him.

Unlike his predecessors, Samaranch decided that he would take up residence in Lausanne. When he arrived, the extent of Berlioux’s influence became clear. Even so, In the early years of his Presidency, Berlioux’s expertise in Olympic matters was to prove vital and she accompanied him to many key meetings.

At the 1981 IOC Session in Baden-Baden, Samaranch publicly acknowledged “the extensive work performed in Vidy and coordinated by our director, Mme Berlioux, to whom, I should like to express my thanks for the enormous amount of work she is doing.”

In 1984 the Winter Olympics in Sarajevo were to be followed by the Summer Games in Los Angeles. “Berlioux is the most powerful woman in sports and a stickler for detail,” recalled Ueberroth in his account of Olympic preparations for LA84. In May 1984, Berlioux was even custodian of the lantern containing the Flame at a Ceremony to launch the domestic Torch Relay in New York City.

Away from the public spotlight however, her relationship with Samaranch had already rapidly turned sour. He is said to have wanted to get rid of her in 1982, but had been dissuaded from doing so by the Romanian member Alexandru Siperco. “The atmosphere became noticeably tense between the Berlioux faction and those supporting Samaranch,” revealed Carrard in his posthumously published memoirs By The Way. “I was being briefed and receiving instructions from both sides.”

At the 1985 IOC Session in East Berlin, Berlioux’s departure was abruptly announced, ostensibly because IOC director of sport Walther Troger announced that he could no longer not work with her. In the next edition of the Olympic Review, it was simply announced that the veteran Swiss IOC member Raymond Gafner had taken over the role with the title of “Administrateur Delegue”, a post equivalent to managing director. But the balance of power had shifted irrevocably back to the IOC President.

When Coventry visited Olympic House shortly after her election, she was greeted by many of the 700 staff. It is exactly a century since the Presidential handover had taken place in Lausanne for the first time when the climate of sport was very different. In 1925, women were still battling for acceptance in the Olympic arena. They competed only in fencing, tennis diving and swimming at the 1924 Paris Olympics. Last summer in Paris, there were an equal number of events for men and women.

In Costa Navarino before the election, Bach had predicted “my successor will face less uncertainty than I had to face when I started my mandate.” Yet as Coventry takes office, she will surely inherit a bulging in tray in a world where political tensions are all too apparent in so many places.

Philip Barker is the editor-in-chief of the International Society of Olympic Historians